RAF Gatow Berlin

RAF Gatow – a former Luftwaffe station – was located at the western end of the city; the airfield boundary faced directly on to the fortified border between the German Democratic Republic (“East Germany”) and West Berlin. For some time we had a direction-finding hut out on this edge of the airfield; the DF operators reported hearing singing coming from the other side of the border on communist holidays.

Records, discovered after the fall of the Berlin Wall, stated that the East German troops stationed there were the ones who would have the task of taking the airfield in the event of an invasion. Typical. Even though we were a member of the four-power agreement, we wouldn’t even be offered the prestige of being attacked by our Soviet partner. We were to be overpowered by troops from the GDR, a country we did not officially recognise. This was so unfair; just not British.

Settling In

One advantage of being in a trade, where the majority of its members were based in one place, was that incoming linguists had no trouble in finding familiar faces. Our arrival, which had been published in Station Routine Orders ('SROs'), was well anticipated. By the time we first landed on the charter aircraft [‘Danair’/’Court Line’?] from Luton at RAF Gatow, our accommodation and watch allocation had already been arranged.

The first thing noticeable about RAF Gatow was the sheer size of the station. It was formerly Göring’s luxury Luftwaffe airfield. Its lavish amenities were still in place some twenty years after the end of the war. The accommodation blocks were large and well-maintained. For the first time since joining the RAF, I was allocated a single room, as was every airman on the base. Originally, I used the communal toilet and wash/shower facilities – just a couple of doors away – before moving into an end room, with its en suite services, when promoted to corporal. The Airbridge Club, containing the bars and a NAAFI [“Navy Army Air Force Institute”] shop for junior ranks, was only a few steps away across the road. Life, as they say, was good.

A Working Linguist

Now based at the unofficial headquarters of the RAF Linguist trade, I soon got into the flow of things. We were so busy that there was no alternative. For the first day or so, we ‘double-banked’ with experienced operators in the ‘set room’. This meant that the newcomer plugged his individual headset into the spare socket of a ‘position’ connected to a VHF radio receiver, hearing the messages at the same time as his proficient colleague. The colleague then guided the ‘logging’ actions. As soon as he believed that you were up to the task, he pulled out his headset, and you were left on your own from then on.

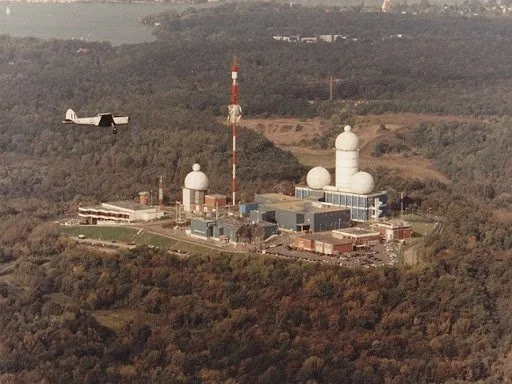

At the time of my introduction to the trade, we Russian linguists were all based in Hanger 4, adjacent to the main runway at RAF Gatow. The German and Polish linguists were already working “up the hill”, i.e. in the unmissable American military listening station of Teufelsberg [Devil’s Mountain], nearer to the centre of the city. Located in the Grünewald forest in the British Sector, this unit – funded by the NSA – was built by US Forces on the top of this artificial hill, which was made up of the rubble from the city devasted by WW2 attacks. Its domed constructions housed a variety of aerials, ensuring excellent ‘line of sight’ reception of signals emanating from surrounding East Germany and beyond.

The Russian language contingent were to move to “The Hill” in the early 1970s, leaving Hanger 4 alone to a specialist RAF Electronic Intelligence (‘Elint’) unit. This hanger now forms part of the “Luftwaffenmuseum der Bundeswehr” [German Air Force Museum] established at Gatow, which was renamed “General Steinhoff-Kaserne” [General Steinhoff Camp] on handover to the German military by the RAF in 1994. Paradoxically, the museum’s exhibits include MiG fighters – inherited from the former East German NVA [National People’s Army] on the breakup of the Warsaw Pact – of the types which would have been the target of our voice intercepts in that very building. But then, nothing was, and remains, normal about Berlin.

In order to put our work into context, a few words of explanation are useful. As professional eavesdroppers, we were in a unique position: we were situated smack in the middle of the Soviet Union’s largest concentration of troops and aircraft. The Group of Soviet Forces in Germany (GSFG) had around fifty permanent and dispersal airfields in the country. At the peak of the Cold War, these housed nearly one thousand combat aircraft and a similar number of helicopters, backed up by transport aeroplanes of various types. Their stated mission: to provide aerial support to Soviet forces in the event of an invasion of Western Europe.

There were also Soviet aircraft based in Poland and Czechoslovakia, whose VHF voice transmissions we could also intercept. This was in addition, of course, to the native East German and Polish air forces, whose interests were covered by our colleagues ‘up the hill’. We could, from time to time, hear Czech language transmissions, but I only knew of one linguist previously trained in Czech. He conveniently forgot his skills, and this was never questioned. We had enough on our plate with the Russian aviators.

The Soviet Air Order of Battle (AOB) in the GDR was divided into two Fighter Corps – North and South – roughly divided along a line level with Berlin. The Northern Fighter Corps consisted of one Fighter Division (interceptor aircraft) and one Fighter-Bomber Division (ground attack aircraft). The larger Southern Fighter Corps was made up of two Fighter Divisions and one Fighter-Bomber Division.

Each Division contained three separate Regiments, where each Regiment had its own airfield. In this way, there were fifteen separate fighter/fighter-bomber stations in an area one-fifth smaller than England. Additionally, the country housed three bomber stations, three transport aircraft bases and numerous helicopter locations.

Every fighter/fighter-bomber regiment consisted of three flights, each holding up to twenty aircraft. At regiment level only two bespoke VHF frequencies would normally be used; one for take-off and landings, the other for tasks away from the airfield (practice airborne intercepts, ground attack, etc.). In the event of joint missions, third or fourth frequencies would be employed.

All these regiment frequencies were subject to change every couple of months, often as a precursor for military exercises. When frequencies were changed, station callsigns and aircraft numbers were also amended. As can be imagined, the cry of “Frequency Change!” brought about a hive of activity in the set room, with operators frantically searching out frequencies and analysts identifying the discovered units. When this happened, the large AOB board in the analyst section behind the set room was wiped clean. It is to our credit that this visual record was generally recompleted within hours, such was the competence of our operators and analysts.

As an example, I once immediately recognised the accent of one of the pilots after a callsign change. It had a distinct central Asian lilt. I had heard the voice only the day before; I remembered his previous number. I immediately informed my superior. The chief warrant officer analyst soon came over, checked my story, and said “Great! That checks out. We know which unit it is”. And I wasn’t the only one who did something similar. Sometime pilots would forget about the change and start to give their old numbers; this hesitation was noted by operators and often was all that was needed for us to identify them. I think it’s fair to say that all operators enjoyed this game, playing their part in adding pieces to the AOB jigsaw.

Like Digby, we worked a shift system on 26 SU. At the beginning this was organised on a simple four-day rota: Day One – Evenings (5pm to 11pm); Day Two – Days (8am to 5pm) & Nights (11pm to 8am); Day Three – ‘Sleeping off Nights’; and Day Four – Off Duty. This system – which was the fall back regime in time of need – was soon replaced by a monthly-based calendar where shifts were adjusted to guarantee one weekend off a month. This was achieved by working consecutive evenings, days and nights in a pattern which, once you got used to it, was a great improvement. It meant that you had to work two night shifts in a row – once a month three – but you got a greater number of days’ rest after the final night stint.

There were four watches – designated A, B, C & D – between which the work was divided 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. I was allocated to C Watch. I like to think that this was the best bunch. It’s difficult to remember exactly, but I believe that each watch had around thirty linguists, headed by a warrant officer and various SNCOs.

Each watch also had a nominated watch officer, who was attached to the unit for two to three years. Although language-trained, they were not linguists. These were normally Flight Lieutenants, who had finished aircrew duties. What they were now doing was known colloquially as “flying a desk”. We had a spate of Vulcan crew members coming on to the unit, if I recall correctly, following the reduction of the RAF V-Bomber force in the late 60s. Their job was administrative. Most realised immediately that it was the warrant officers/SNCOs who made the unit tick and were happy to sign whatever was put in front of them.

From time to time a new officer would come in and question the analysts’ way of working. They soon learned that this was a foolish path to follow; on one occasion GCHQ sent a request for one newcomer watch officer not to interfere. (Our long-serving seniors had influential friends everywhere). The unit’s Wing Commander read the riot act to the officer concerned and peace was restored.

Talking of watch officers, one stands out in my memory. Flt Lt Bob Moss was my first watch officer at Gatow. A fellow Yorkshireman, he was popular with everyone. He took great interest in all our work. He once tried to replicate our efforts, but soon gave up, expressing deep admiration for our skills. Most of all, I recall one time in the middle of the night, when we were extremely busy (and watch officers were normally asleep in the back), he came round asking whether we wanted tea or coffee. Assisted by the watch warrant officer, they then made hot drinks for everyone. This gesture added even more esteem to our valuation of him.

The set room was laid out in rows of receivers with attached tape recorders. Each receiver was tuned to an established frequency. Should a message come through on its loudspeaker, this activated the tape and it started recording. Until we ran out of operators, we would log every frequency ‘live’. Thereafter, should there be more active sets that available operators, the frequency would be passed over to the large bank of recorders at the side of the set room. Here one of our linguist crew was responsible for ensuring that all frequencies were being recorded correctly. He would put an announcement on the beginning of the tape and write the required details on the tape envelope. These tapes would be then be transcribed later, once the live traffic had receded.

In summer months, we could spend all night going through tapes in the separate transcription room and still not finish the backlog before the Russkies started flying again the following morning. We all got a mid-shift break, of course, but concentration could easily waver after hours of transcribing. But the longer we did it, the more we got used to it and the quicker the shifts passed by. Moreover, if there was no work to do – in periods of bad flying weather and during Soviet holidays – the SNCO in charge of manning the set room would send several away. This was called “stand down” and his lists were meticulously followed; we always knew when it was our turn to be ‘stood down’ next.

Up to now, mention has been made only of airmen. This is because, up to 1978, the Linguist trade was 100% masculine. The first WRAF recruits started language training around the time I left the RAF, so I had no experience of working alongside female colleagues. There was one exception, however. During my second stint at Gatow, we had one female watch officer. She was a Squadron Leader, the daughter of an Air Vice-Marshal. I now admit that – after Bob Moss – she was my second-favourite watch officer. She had a great way with subordinates, which is not a factor that could be attributed to some other officers with whom I worked. It’s just a pity that I cannot now remember her name.

The RAF Gatow camp itself had been totally male dominated until early 1970, when the first batch of WRAF personnel to be based there arrived. I remember the day clearly as, just by chance, it coincided with my first duty as Orderly Corporal on the camp. One of my allotted tasks in this role was to ensure that the bars in our Airbridge Club were closed at 11pm. When I entered, I recall noting how many airmen – unusually for a weekday evening – had put on collar and tie to drink in the functions room. For the next few months, until my departure, it was common for the WRAF ladies to say “Hey, it’s the Orderly Corporal” when they saw me.

Back in Hanger 4, to assist us in our work, we had so-called “Frequency Boards” available for each target unit. (Every regiment had a recognition code for our AOB, beginning TBxxxx. TB101A, for example, was a fighter regiment in the Southern Fighter Corps. This recognition code would be the title of the board). These aids would contain the temporary callsign of the airfield’s controller (a random Russian word) and the list of three-figure numbers used by the pilots of the aircraft on the unit’s strength. The information on these large cards was helpful in our work, but the best entertainment came from reading the comments which had been added by linguists on the back. The contributions were rude and highly personal at times, but very funny.

As time went by, there were two things that animated me: new carbon sheets and tinned tomatoes.

The act of logging and transcribing was completed by writing what we heard on A4 size landscape pads. At the top of each page was a section where details including the intercept station number (26 SU was UKA277), operator number (mine was 780), frequency, date, and page number were to be filled in. Lined boxes underneath were used for writing in the received text and time. The pad pages were thin, to allow two carbon sheets to be inserted. In this way, three copies of each page were generated. We used the bottom copy internally to generate analyst records, so the better the copy you made, the easier it was for colleagues to read. Also, experience showed that new carbon sheets gave a firmer base for writing on. Worn carbons were therefore to be avoided. If I came across a new box of carbons, I would often sneakily take extra sheets to hide beneath my desk. I became very fussy about this.

By six o’clock in the morning on a night shift, you were already thinking about breakfast. Full English, of course. Most of all, whether there would be tinned tomatoes on the buffet. All the other items were constantly available, but for some unknown reason, tomatoes only made it around two days in seven. I had a colleague on another watch who also craved tomatoes (especially good when combined with fried bread). If he was on the day shift taking over from us, he would let me know “yes” or “no”. The affirmative message would ensure that I went to bed happy; a negative report temporarily depressed my spirits.

Such small things as fresh carbons and tinned tomatoes were therefore highly important to a fully-fledged linguist.

I was now getting better and better at the job. Before my time, the trade used to run a system of “Star Operators”. The very best loggers were known as ‘5-Star’. I soon achieved (an unacknowledged) ‘4-Star’ level. The capabilities of each individual were known; the fact that I was requested with increasing regularity “Can you listen to this?” by others during transcription work indicated my growing status amongst colleagues. (I was not pretentious about this. I would similarly ask for others’ interpretations of questionable messages. We worked as a team).

There was a demonstrable way of proving your operator status, however. That was when you were trusted to ‘live log’ the main navigational frequencies. These air traffic channels had fixed, unchanging frequencies. The callsigns used by the stations were also permanent. As far as we were concerned, there were two channels: “Internal Nav” on 135.25 MHz and “Main Nav” on 124.00 MHz. Internal Nav covered the GSFG air movements within the area of East Germany; Main Nav was used for flights by all air forces within the Warsaw Pact area.

Less than a year after joining 26 SU, I was the watch’s chief operator on the Internal Nav channel, although I could just as easily switch to Main Nav. At busy times, it was sometimes necessary to ask a capable colleague to double-bank with you, to allow you to catch up. The logging routine meant that, at times, a stack of half-completed pads would accumulate. Your colleague’s assistance would allow you to go back over the logs and fill in the gaps; rip off and file the completed pages; then prepare another stack of pads with fresh carbons for further use. This completed, it was your partner’s turn to catch up, when you took back control. This was teamwork at its very best; just a taster for what was to happen in late August 1968.

Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia

On 21 August 1968, following a watch day off, our members we were all rudely awakened individually at around two in the morning and told to report immediately to Hanger 4. “They’ve invaded Czechoslovakia” we were told. When my colleague Mick Clubley (of Chelsea supporting fame) was informed, he answered “Have they invaded Berlin?” “No” he was told. “Then wake me up when they do” was his response. Nevertheless, he joined us all shortly afterwards in a crowded set room.

The chief warrant officer analyst soon arrived and ordered “Put the best operators on the navigational frequencies”. Although this wasn’t my watch, I was directed to the Main Nav console. I was only a Junior Technician with just over one year’s experience, whilst others around of superior rank had longer service. I was delighted that I had been chosen, yet anxious lest I failed to meet their confidence in me.

Although other frequencies were active, as their air forces backed up the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact countries, it was the messages on the main navigation channel which gave the leading indications of the actions of the invasion armies. This was the reason why particular attention was being paid to this frequency.

One thing was immediately apparent when I plugged in my headset; I could hear normally inaudible ground stations. For the first, and only, time in my linguist career, the Soviet Air Force had put an airborne relay aircraft in a circuit above the Czech border. Its effect was to double the VHF communications range for our radio intercepts.

Although I hadn’t had a lot of sleep, I was wide awake during my work. Without doubt, this was my “finest hour”. I had to get a colleague to help with preparing and separating my log pads; the radio chatter was non-stop. Sometimes he took over for a short period whilst I caught up, but I was generally in the driving seat. All the time I was aware that groups were standing behind my position. They were taking my log copies as soon as they appeared and were analysing events on the run. When things started to calm down, I took a break. The watch warrant officer came over to say “Well done!” to me.

The section had two so-called “Spec Transcribers” on the permanent day shift, whose job it was to transcribe messages of special interest. These were the modern-day equivalent of the former ‘5-Star’ operators. I was later informed that one of them had been simultaneously listening in to the frequency on another receiver. Reportedly he said “Leave Leo there, he’s doing OK”. This, from one of the spec transcribers, was the nearest thing to words of praise you would ever get out of them.

Just over a year later, I received accelerated promotion to the rank of Corporal. Normally this took three years at the earliest after qualifying as a Junior Technician. I was promoted after two-and-a-quarter years. Although it was never stated, I am convinced this happened because of my input during our intercept coverage of the Czechoslovakia Invasion of August 1968.

Two examples of my logging skills of special significance still stand out in my memory.

One time, a transport pilot, having landed, sent out a weak message “Order meals for four persons”. Such comments from the ground were often ignored or missed by operators, but I managed to make it out. Shortly thereafter, the chief analyst came by and queried “Is this right?”. I answered that I believed so. He had it checked by a spec transcriber and made a point of coming back to say that I had heard correctly. This was an important detail. Knowledge that four crew were involved helped him identify that this was a new type of helicopter now active in East Germany. He was very pleased and thanked me once more for my good work.

Later, it was believed that a fighter-bomber had crashed and we were asked to keep an ear out for any search activity on the navigational frequencies. Then I heard a message “The pilot xxxx near the lake”. I couldn’t make the missing word out when live logging, but a quick spec transcription confirmed the word: it was “perished”. I had found the desired crash reference.

If I didn’t know this before, I now was convinced that I had found that missing thing which, at last, I was good at. I could have gone through life never experiencing this satisfaction. The Army used to have a recruiting slogan “If you have it in you, we’ll bring it out of you”. This applied equally to the Royal Air Force.

Working ‘Up the Hill’

At the time of my return to Gatow in 1971, the full RAF linguist contingent was now permanently based ‘up the hill’, i.e. at the specialist listening station atop of ‘Devil’s Hill’, i.e. Teufelsberg. Under the old system, newly qualified in German, I would have been one of the lesser number of non-Russian specialists operating in the separate RAF section there. In the period that I had been away training at Luffenham, the expansion and complete reequipping of the British side of the building had been completed, now providing room for all our tradesmen in a single place.

As already mentioned, the station at Teufelsberg was constructed by US Forces, financed initially by the American National Security Agency (NSA). The expansion to include the RAF section was paid for by GCHQ, with UK Government support. The building – with its unmissable ‘mushroom’ aerial towers – was surrounded by a high fence with armed guards on patrol. [It was once reported that a trigger-happy guard shot dead a local pensioner who was collecting wood, but this may have been an urban myth]. The main entry was controlled by US Military Police, where the British went off to the right and the Americans to the left. Entry thereafter into our section was through an electronically controlled gate, manned by an RAF Policeman, who handed over personally numbered identity cards complete with lanyard. Each individual’s card was colour coded to denote which areas of the building he could enter.

Although we were in a building run by the US Military, our USAF counterparts were not housed with us. They had a separate station in the American Sector but were in permanent contact with us via a secure telephone link. We had little interaction with the US side at Teufelsberg – probably for security reasons – although we utilised their ‘Chow Hall’, located in an open access central section, for meals. The food there was not always to our taste (just how often can you eat hamburgers?) but I recall a couple of items I never missed, if available. They had packed “Drinking Milk” which was uniquely delicate in taste, whilst I developed a lifelong liking for meatloaf from dining there. I also recall seeing an item in the cold section which only the US Forces could offer: a packet labelled “Genuine Artificial Ice Cream”.

I was allocated to D Watch this time around, now continually working on a 28-day shift cycle. I didn’t know what to expect when I arrived on the first day. I hang around waiting for German work, when the watch Warrant Officer told me not to be choosy; he’d prefer me to concentrate on Russian. This suited me. Within a few days I was back on the main navigation frequency. I remember that, in this position, I more than once had two log pads on the go at the same time; one with Russian, the other with German. This could only be done at quiet periods, otherwise it would send you crazy. The accepted routine was that, if the operator on the frequency heard a transmission in another language, he’d yell out “GC on Main Nav!” for German [GC=German Communist] or “PL on Main Nav!” [PL=Polish]. A specialist in the particular language would then let it be known that he’d got it and the operator could go back to concentrating on the Russian intercepts. In the event, it was soon as if I’d never been away – only the watch had changed. In the duration of this posting, probably less than 10% of my work completed was on German intercepts.

Towards the end of my three-year stint, it was decided by NSA & GCHQ that perhaps it could be worthwhile looking into the matter of duplication of work by the two separate US & British SIGINT units in Berlin. To this end, a two weeks’ experiment was undertaken, where the possibility of mutual use of an American rapid reporting routine was tried. I was one of the team of eight SNCOs from the British side chosen to take part.

In preparation I went to visit the USAF listening base at Lichterfelde to familiarise myself with their system. Unlike us, they employed a senior, experienced “Line Walker” who was constantly monitoring the work of his team, whilst walking up and down the set room. He was in microphone contact with both his operators and his analysis colleagues. He would report any significant happening to his backroom team, who would pass the message to a waiting teleprinter operator to send off to NSA immediately via a secure link. It has to be admitted that their methodology had ours beaten for speed of action. However, it must be added that their system was not foolproof. Mistakes were sometimes made and significant events missed. Our reporting system was correspondingly slower, but we were more thorough in the analysis and validity of our conclusions. A combination of both approaches – if feasible – therefore made sense.

Two SNCOs per shift were trained in working this technique, where I tended to be the leading administrator on our team. The USAF sent over a teleprinter operator – complete with his own machine – who worked the same shifts as us for continuity. In this joint operation – called “Division of Effort” – my job was to pass the brief activity messages to him for transmission. In accordance with standard US Forces routine, these were called KLIEGLIGHT Reports. The operator was used to the required style and content, so this helped considerably. All this was going on whilst the rest of the watch worked in our usual procedure. However, they were all aware of what I was doing and so assisted me throughout, without us having to go to the extreme of copying their ‘Line Walker’ system.

After the completion of the experiment, the USAF teleprinter operators left us and we went back to normal operations. I believe that the results of our co-operation trial were sent to both NSA and GCHQ for analysis, but as I never returned operationally to Gatow after 1974, I do not know if our efforts led to any amendments of operational procedure on either side. The one thing I do remember was the comment of the American teleprinter operator at a busy time during the test: “God, you guys are good!”. I’ll take that as a positive.

A Spy in our Midst

When I was preparing for my promotion examinations to corporal, I was told to go and see the unit’s trade training instructor, Cpl Geoffrey Prime. I recall that he had a separate section in the mezzanine structure of the hanger. There was nothing extraordinary about him, just a person who preferred to keep himself to himself. The next time I saw him was a few years later, on a 1976 visit to GCHQ. I was there with another instructor from Training Wing at North Luffenham. My colleague said to me “Do you remember Geoff from Gatow?”. By then Geoffrey Prime had left the RAF and had worked his way up to a Higher Intelligence Specialist position at Cheltenham. I remember that Geoff just nodded to us and went back to the paperwork he was reading. As I said, he was not the most communicative of people.

According to the report on Wikipedia, Geoff first contacted the Soviets, offering to act as a spy, by throwing a message to a sentry from the British Military Train in 1968. He insisted that he was making his offer due to ideological motives. Apparently, he received training from the KGB whilst still in the RAF in Berlin. (This meant that I was on the same camp as him when this was happening). When he left the RAF shortly thereafter, the KGB encouraged him to join GCHQ. It was here where he would carry out the bulk of his espionage work.

He resigned from GCHQ in late 1977, although there is a suspicion that he carried on his spying work until 1982. What is most amazing about this story is that, when he was arrested that year, it was because his escalating paedophile activities had driven his wife to contact the police; his espionage (which she also knew about) was secondary to her at that time.

With his depth of knowledge, there is no doubt that Geoffrey Prime’s disclosures caused major damage to UK’s intelligence gathering efforts, as well as causing severe relationship problems with our US partners at NSA. His case was the subject of a Security Committee investigation and report.

He was sentenced in total to 38 years’ imprisonment, being released halfway through in 2001. Now permanently on the Sex Offender Register, he must register with police wherever he lives. At least two of his secret locations have been discovered, although there is no record from recent times.

What makes this case so interesting to me is that, sometime during 1969, a major RAF Police investigation of the personal lives and connections of some linguists took place at Gatow. We never knew the trigger for this, but it coincided with a short article written by a former Russian linguist in the controversial ‘Oz’ magazine of that time. The only person singled out from questioning was one linguist who admitted that he was homosexual. He was then quietly taken from the station and allowed to leave the RAF. (Although homosexuality was not against the law then, it was still reason for instant dismissal from the military, particularly where classified work was concerned, as it was judged that the individual could be open to blackmail or coercion. In this case, we all believed that our former colleague “pulled a fast one”, as we knew that he was desperate to leave the RAF. He saw an opportunity and took it). Nevertheless, if this investigation included all those connected to our trade, was an opportunity to perhaps head off Geoffrey Prime’s activities missed here?

Please note that the copyright of this page belongs to Brian Leonard (https://www.bltalk21.co.uk) and no part may be reproduced from this site without his permission.